What Do We Really Know About Gregorio Del Pilar, Philippine History's Baby-faced Assassin?

This week, Goyo: Ang Batang Heneral continues its run in theaters nationwide. The film, as we all know by now, tells the story of Gregorio del Pilar, the Boy General of the Philippine Revolution and one of the most well-known figures in Filipino history.

As anyone who's seen it can attest, the film is deliberate about its take on the life of its titular hero, on which there isn't really a singular authoritative resource. The film's director, Jerrold Tarog, said it himself: “Nobody really knows how Goyo was. Nick Joaquin, Jose Alejandrino, Teodoro Kalaw and Isaac Cruz all saw Goyo differently."

This measure of abstractness gave the film room to flesh out its own vision of Gregorio del Pilar. But while it does admit to taking liberties, it is also thoroughly and painstakingly researched, based on the several accounts of del Pilar's life that do exist.

Such is one of the film's joys: diving in and wading through the facts and fact-based fiction to find some telling tidbits of our history. Here are a few such tidbits from historical accounts of del Pilar's life, which should help to give you a better idea of who Goyo really was, or might have been.

(Spoiler warning: While these are historical anecdotes, some of them appear in the movie. So if you'd like to come in clean for Goyo, proceed no further. And while you're at it, forget everything you learned in high school history class.)

Goyo, the Aguila of Bulacan

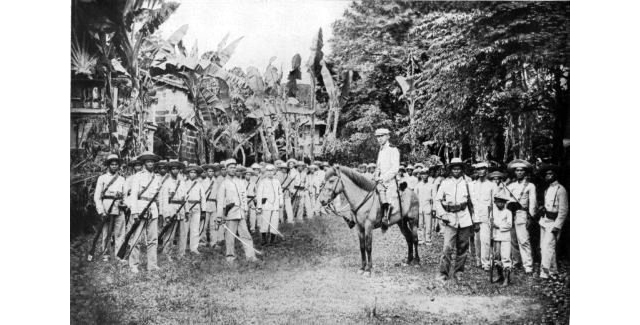

Gregorio del Pilar is fondly remembered as a bold and daring soldier, and there are quite a few stories and anecdotes that give credence to this image of him. He has his fair share of documented wartime exploits and acts of bravery during the Revolution. Authors Nick Joaquin and Teodoro Kalaw recall two:

The first was that Goyo, who wanted a Mauser rifle to replace his Remington, ambushed a friar and his escort detail on the way to Malolos, killing them all singlehandedly—supposedly. The truth was less glamorous but more interesting: he managed to shoot one cazador while the rest fled, leaving their rifles and money. He then distributed some money to his men and used the rest to buy cloaks and blankets for them.

The second story goes that Goyo and his men dressed up as women to sneak into the town of Paombong, where they ambushed the garrison during mass. There is no evidence, however, that they did disguise themselves—all we know is that they snuck into town at night. Goyo himself stood at the plaza and shot anybody trying to approach the windows of the garrison where the cazadores were stationed.

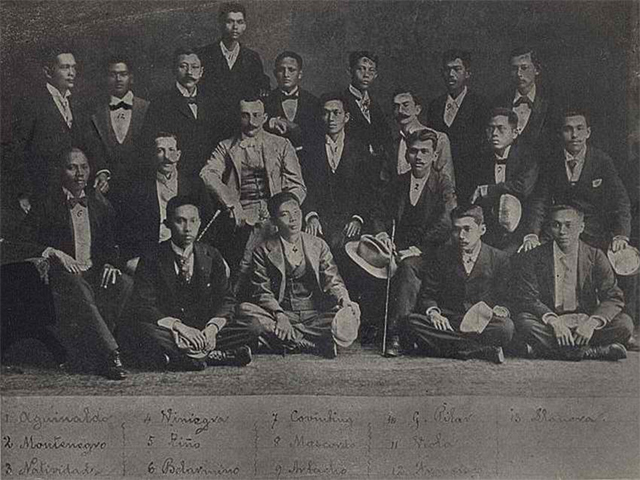

Nevertheless, these stories showed Goyo’s bravery, compassion, and vanity. Artermio Ricarte noted that the feat in Paombong “exalted him to the horns of the moon." And by proving his skills in Paombong, he scored a spot in Aguinaldo’s inner circle.

Goyo, the Vain Cassanova

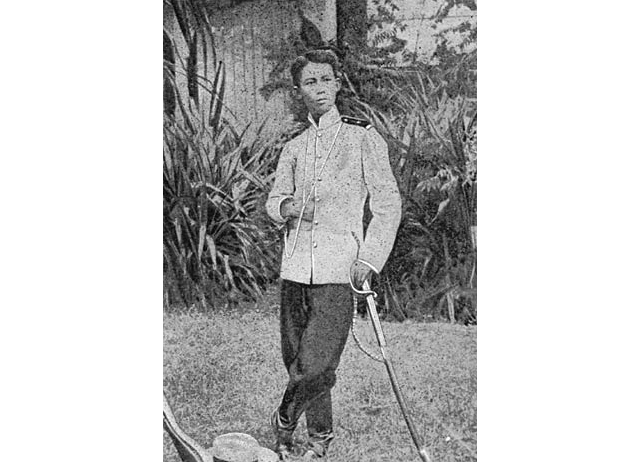

There's a reason that Nick Joaquin described Goyo as “the Byron of Bulacan." He was the definitive Byronic hero: proud, defiant, and suave. He created a flag for himself and was always dressed impeccably. He had a gold tooth fitted during his stay in Hong Kong. His aide-de-camp, Vicente Enriquez, recalled during Tirad that he “wore a new khaki uniform with his campaign insignia, his silver spurs, his polished shoulder straps, his silk handkerchiefs, his rings on his fingers. Always handsome and elegant!”

Goyo was also a Romeo with a Juliet in every town. His list of women was long and included the daughter of Bulacan’s civil governor, a sister of Col. Jose Leyba, and Felicidad Aguinaldo, sister of Emilio.

Perhaps the most famous of these loves was his last, Remedios Nable Jose. Goyo carried a lock of her hair and letters wherever he went, even during his fateful retreat up north. Kalaw remarked that Goyo pursued his loves “without scruple and almost publicly, though he had already distributed his heart in fragments among half a dozen girls.”

But because of his vanity, he ended up neglecting the war around him. Both Joaquin and Kalaw note that he spent his time chasing women instead of preparing for an attack in Dagupan. Even when the writing was on the wall, Goyo seemed unconcerned. When San Fabian was being bombarded by American ships, Goyo was instead writing to a relative to request for the finest riding boots. When informed of noise that sounded like rifle shots, Goyo brushed it off and said that they mistook people pounding rice for rifles. This callousness proved fatal: by the next day, Americans were pursuing them, forcing them to retreat in disarray.

Goyo, the Arrogant Hatchetman

As Aguinaldo’s favorite officer, he was despised by everybody else. During a military parade to commemorate the Malolos Republic, he had a spat with General Isidro Torres, prompting Goyo to ride to the plaza on his white horse to proclaim that Torres had “no command where [he] commands.” Jose Alejandrino, Antonio Luna’s aide de camp, recalled Goyo as “a young, pretentious general who … spent days and nights at fiestas and dances which his flatterers offered in his honor.”

Joaquin also refers to him as “Aguinaldo’s hatchet man.” He was sent to arrest Antonio Luna, and then tasked to liquidate the Bernal brothers—a task he performed unflinchingly. He arrested Luna supporters like Vivencio Concepcion, demoralizing the army. He took over in Dagupan, not to defend against the Americans, but against Ilocanos who might rebel due to the Luna murder.

How did Gregorio del Pilar die?

Nick Joaquin once said that if we ever had an American-made hero, it was Gregorio del Pilar. Accounts of his death romanticized the battle and still capture popular imagination to this day. The notion of Goyo being the last to fall in Tirad Pass after trying to secure his men’s retreat was a fabrication written by American newspapermen who weren’t even there for the battle.

The real story was much less glamorous. Goyo, curious to see the American position but unable to due to the tall grass, ordered a ceasefire so that he may try to look. He stood up to get a better view and was shot in the neck, dying instantly. Both Vicente Enriquez and Telesforo Carrasco, who were with Goyo during the battle, corroborate this story in their memoirs.

In the end, Goyo died and the Americans crossed Tirad before lunchtime. Aguinaldo was captured soon after in Isabela, shortly after his birthday.

It's never easy to accurately detail the life of long-gone historical figures, Gregorio del Pilar included. There's a lot to sift through: memoirs, news reports, accounts, biographies. That time has muddled up some details certainly does not help. But it’s important for us to take what we have and discern what we can—to differentiate reality from propaganda—not only for posterity, but so yesterday can guide us better today.

Sources:

Nick Joaquin (2005). A Question of Heroes. Mandaluyong City. Anvil Publishing, Inc.

"Gregorio del Pilar". National Historical Commission of the Philippines.

Xiao Chua (May 9, 2017). “Ang huling pag-ibig ni Gregorio del Pilar” GMA News Online.

“11 Things You Never Knew About Gregorio Del Pilar”. Filipiknow.